This month’s Australian Fairy Tale Society faery tale is Little Red Riding Hood – and it’s fascinating just how many versions there are. In some, she and her grandmother are eaten by the wolf, and that’s the end of the story. In some she is the victim, rescued by the huntsman or woodcutter. In others (my favourite ones), she rescues herself and her grandmother.

This month’s Australian Fairy Tale Society faery tale is Little Red Riding Hood – and it’s fascinating just how many versions there are. In some, she and her grandmother are eaten by the wolf, and that’s the end of the story. In some she is the victim, rescued by the huntsman or woodcutter. In others (my favourite ones), she rescues herself and her grandmother.

The best known is Charles Perrault’s Le Petit Chaperon Rouge (Little Red Riding Hood), published in 1697, complete with the classic “Grandmother, what big ears you have…” exchange. Yet despite this being the first written version (as opposed to older versions told orally, including tenth century French tales where Red was the hero who outwitted the wolf), most people remember the ending the Brothers Grimm added to this story in 1812.

Perrault’s version is deeply creepy – the Wolf, masquerading as Grandma (and having already eaten her), invites Red into bed with him, she takes off her clothes and climbs in, then he eats her. The end. No rescue, no saving herself or her grandmother, no punishment for the wolf, no redemption. Instead, it ends with a moral from the author:

And, saying these words, this wicked wolf fell upon Little Red Riding Hood, and ate her all up.

Moral: Children, especially attractive, well-bred young ladies, should never talk to strangers, for if they should do so, they may well provide dinner for a wolf. I say “wolf”, but there are various kinds of wolves. There are also those who are charming, quiet, polite, unassuming, complacent, and sweet, who pursue young women at home and in the streets. And unfortunately, it is these gentle wolves who are the most dangerous ones of all.

Fortunately the Brothers Grimm, despite usually loving a bit of death and cannibalism, allowed Red and her gran to be rescued by the huntsman (in other versions it’s a wood cutter), who cuts open the wolf so they can emerge, unharmed. But the Grimms being the Grimms, they couldn’t resist adding that Red had learned her lesson, and would never stray from the path again:

And Little Red Cap thought to herself, “As long as I live, I will never leave the path and run off into the woods by myself if mother tells me not to.”

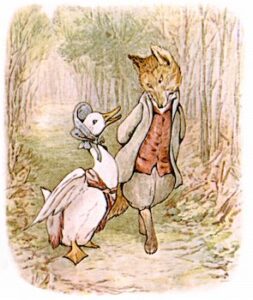

In other versions, the wolf makes Red eat some of her grandmother’s flesh, or tells her to take off her clothes and throw them in the fire before getting into bed with him. In another, Red is saved not by a woodcutter but by the magic of her hood, which burns the wolf’s mouth when he tries to eat her, and in still others, after Red escapes, a second wolf stalks her through the woods, but much wiser now, she and her grandma outwit him, and he ends up drowned, or dying because they cut open his stomach and fill it with rocks. (And people think faery tales are for children!) Then there’s the adorable Beatrix Potter version, The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck, where a cunning fox replaces the wolf, and Jemima is the sweet innocent Red about to be eaten.

In other versions, the wolf makes Red eat some of her grandmother’s flesh, or tells her to take off her clothes and throw them in the fire before getting into bed with him. In another, Red is saved not by a woodcutter but by the magic of her hood, which burns the wolf’s mouth when he tries to eat her, and in still others, after Red escapes, a second wolf stalks her through the woods, but much wiser now, she and her grandma outwit him, and he ends up drowned, or dying because they cut open his stomach and fill it with rocks. (And people think faery tales are for children!) Then there’s the adorable Beatrix Potter version, The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck, where a cunning fox replaces the wolf, and Jemima is the sweet innocent Red about to be eaten.

Of course, threads of the story can be traced back thousands of years, from Greek fables to Asian stories of The Tiger Grandma and Grand Aunt Tigress. There are so many intriguing rabbit holes you can fall down if you start researching more of the echoes and threads of this tale – which is what we do each month for our Australian Fairy Tale Society meetings (some in person, some by zoom so everyone can attend). And my writer friend EC Hibbs does a wonderful video series about faery tales, called Truth Behind the Tale – you can see her Little Red Riding Hood one here.

Even more fascinating to me are the new stories, from entire novels inspired by the original, such as Demelza Carlton’s Hunt and Melanie Cellier’s The Princess Fugitive, which I have on my tbr pile, to storybook versions like Susannah McFarlane’s reimagined tale, in her book Fairytales for Feisty Girls. In this version Red – whose name is actually Lucy – collects and studies plants and wants to be a botanist, and learns herbalism from her wise woman grandma. Between them, how could they not defeat a wolf?

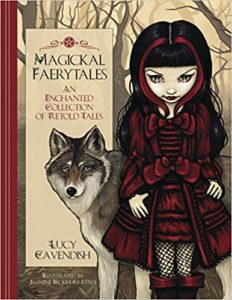

But my favourite version of Red Riding Hood is by Lucy Cavendish, in her gorgeous hardcover book Magickal Faerytales: An Enchanted Collection of Retold Tales. It’s full of magic and wisdom, of the links of maiden mother crone (so unusual for a faery tale to have loving relationships between mother, daughter and grandmother!), of a grandma who is a wise woman in the deep dark woods, and a heroine on the cusp of maidenhood who is not so gullible and unaware as her earlier incarnations, not so passive. It’s about choice, and choosing your path and your destiny, and love and strength and destiny… And it’s illustrated so beautifully by Jasmine Becket-Griffith, as is the gorgeous, magical Faerytale Oracle deck they created together…

But my favourite version of Red Riding Hood is by Lucy Cavendish, in her gorgeous hardcover book Magickal Faerytales: An Enchanted Collection of Retold Tales. It’s full of magic and wisdom, of the links of maiden mother crone (so unusual for a faery tale to have loving relationships between mother, daughter and grandmother!), of a grandma who is a wise woman in the deep dark woods, and a heroine on the cusp of maidenhood who is not so gullible and unaware as her earlier incarnations, not so passive. It’s about choice, and choosing your path and your destiny, and love and strength and destiny… And it’s illustrated so beautifully by Jasmine Becket-Griffith, as is the gorgeous, magical Faerytale Oracle deck they created together…

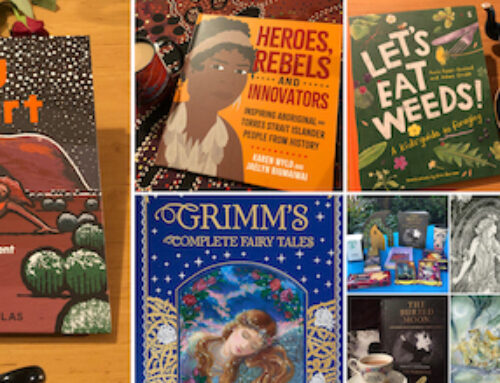

Some of the many versions…

1697: Little Red Riding Hood by Charles Perrault.

1812: Little Red Cap by The Brothers Grimm.

(And their later version, with a second wolf to be defeated.)

1883: The False Grandmother by Antonio de Nino.

1885: The Story of Grandmother by Paul Delarue.

1888: The True History of Little Golden Hood by Charles Marelle.

1889: Perrault version by Andrew and Nora Lang in The Blue Fairy Book.

1890: Marelle version by Andrew and Nora Lang in The Red Fairy Book.

1908: The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck by Beatrix Potter.

1956: The False Grandmother by Italo Calvino.

[…] You can check out all the versions I read, plus others, here. […]